Il Sannio si configura

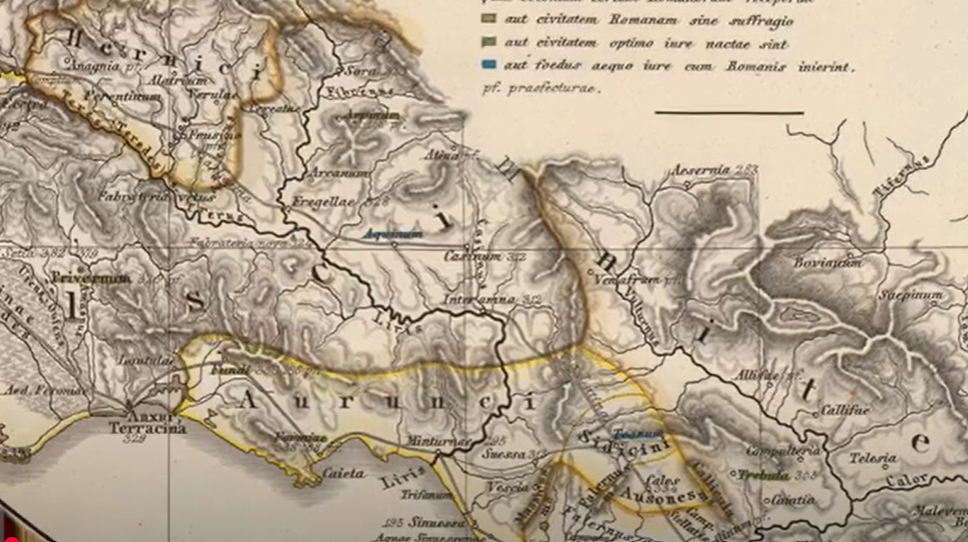

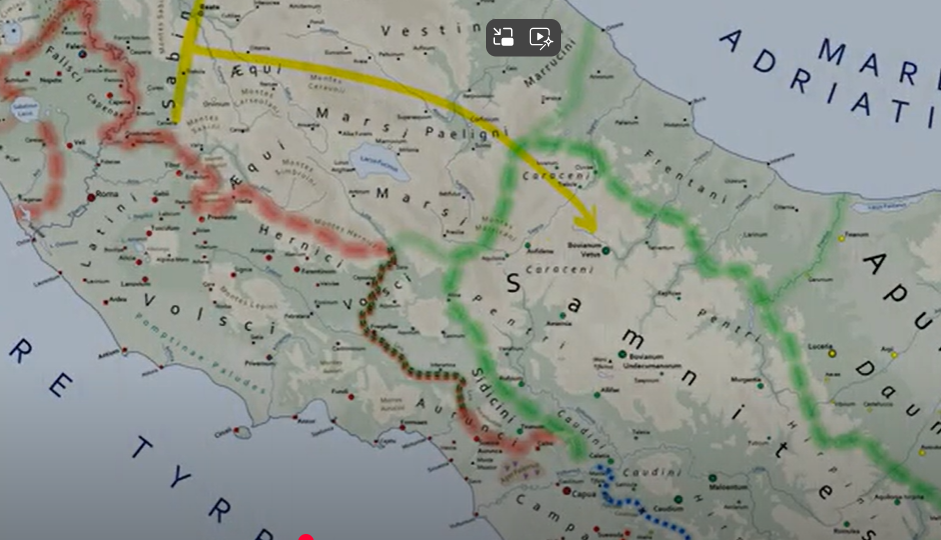

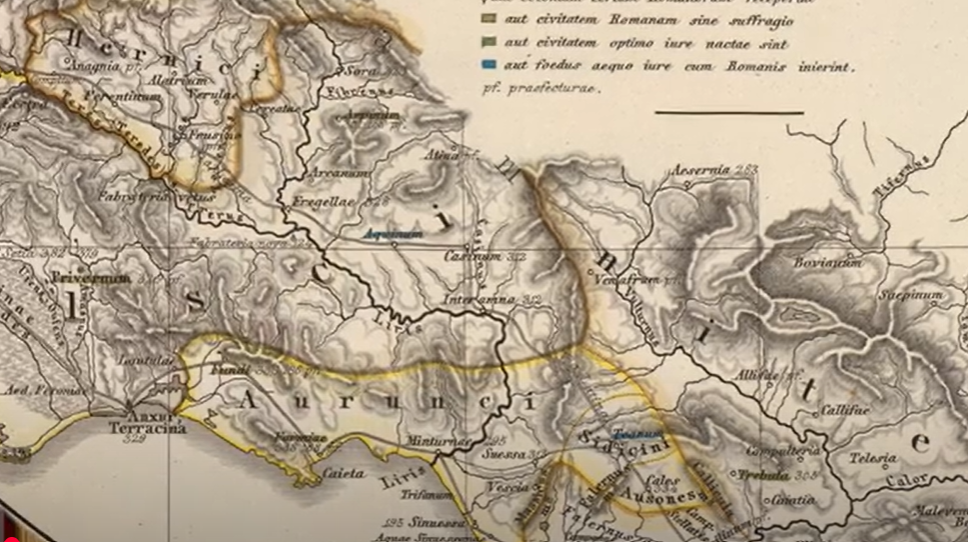

Il Sannio si configura come un altopiano situato nel centro dell’Italia meridionale. È delimitato a nord dal fiume Sangro e dai territori dei Marsi e dei Peligni, a sud dal fiume Ofanto e dai territori dei Lucani, a est dal Tavoliere delle Puglie e dal territorio dei Frentani, e a ovest dalla pianura campana e dai territori dei Sidicini, dei Latini e degli Aurunci.

Il Sannio è prevalentemente montuoso, con formazioni di calcare e dolomia che, a causa della loro conformazione e altitudine, rendevano il transito difficile, ma offrivano rifugi sicuri per le tribù sannitiche. La Majella era il rifugio dei Caraceni, i monti Irpini degli Irpini, il Monte Taburno dei Caudini e il Matese dei Pentri. Dai rilievi montuosi e dalle sorgenti si originano numerosi corsi d'acqua, indispensabili per l’agricoltura e la pastorizia, praticate su terreni in prevalenza poco fertili, anche a causa di condizioni climatiche avverse, come inverni rigidi, gelate tardive ed estati siccitose.

La difficoltà nel produrre risorse alimentari sufficienti per una popolazione in crescita spinse i Sanniti a migrare verso le fertili pianure circostanti, spesso entrando in conflitto con gli agricoltori locali che consideravano le greggi una minaccia per le coltivazioni. Nonostante un’efficiente rete viaria, di cui restano alcune tracce come la strada che attraversava il Matese per collegare Alife a Telesia e Beneventum, i Romani impiegarono più di settant’anni per conquistare e integrare il Sannio.

Nel IV secolo a.C., il fiume Sangro segnava il confine settentrionale del Sannio, che includeva territori come il Monte Meta e la valle di Comino.

Durante questo periodo, il Sannio si espanse verso il fiume Liri, includendo città come Aquino e Venafro. A sud, il confine era segnato dal fiume Ofanto, mentre a est città come Teanum Apulum e Canusium non facevano parte del Sannio, a differenza di Luceria, che probabilmente vi apparteneva.

Secondo la tradizione, i Sanniti erano discendenti dei Sabini, che si spostarono nel Sannio attraverso un rituale noto come "Ver Sacrum". Questo rituale prevedeva che i giovani consacrati alla divinità Camerta lasciassero la loro tribù per fondare nuove comunità sotto la guida di un animale sacro, spesso rappresentato simbolicamente su un vessillo. La necessità di praticare il Ver Sacrum era probabilmente legata alla sovrappopolazione.

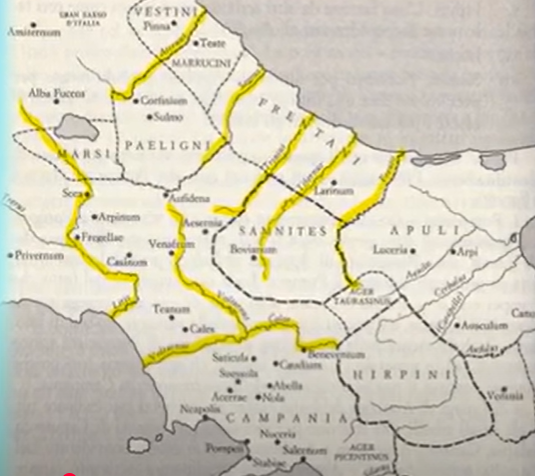

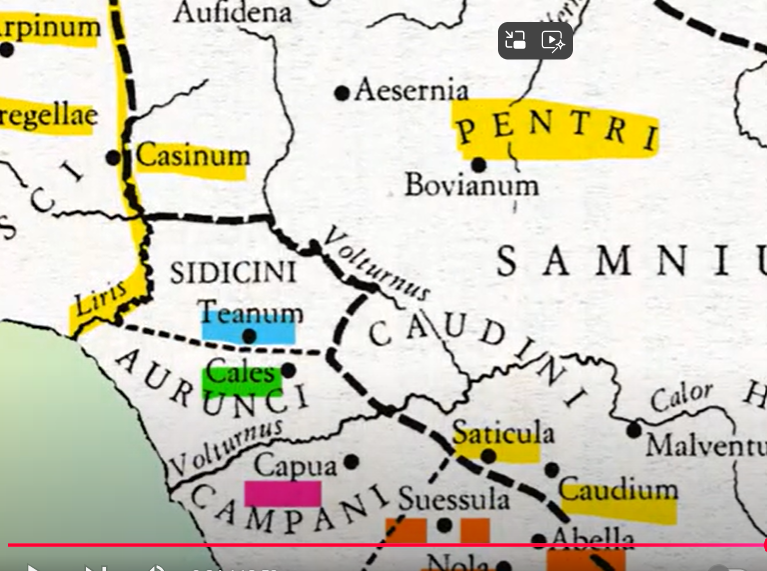

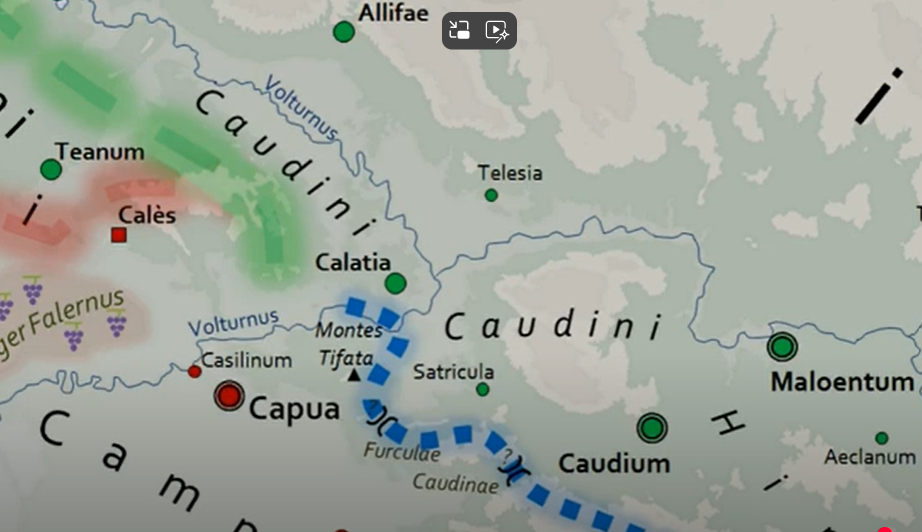

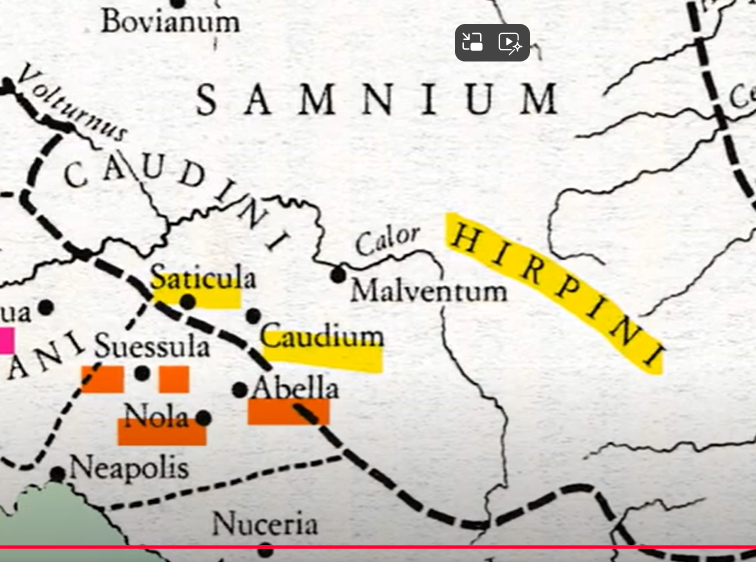

Le principali tribù sannitiche erano i Pentri, i Caudini e gli Irpini. I Pentri, popolazione montanara, occupavano la regione del Matese e le valli dei fiumi Trigno e Tiferno. I Caudini, situati tra le montagne e la pianura campana, erano i più urbanizzati e influenzati dalla cultura greca. Gli Irpini, detti "uomini-lupo", abitavano le vallate dell’Ofanto, del Calore e del Sabato, confinando a nord con i Pentri e a sud con i Lucani.

Dopo le guerre sannitiche, i Sanniti persero gran parte del loro territorio a favore di Roma, mantenendo una parziale autonomia fino alla Guerra Sociale, quando ottennero la cittadinanza romana. Da allora, le tribù sannitiche furono integrate nella struttura amministrativa romana.

Le prime menzioni dei Sanniti si trovano negli scritti greci del IV secolo a.C., che li descrivono come abitanti delle città di Tifernum e Mistai. Il loro territorio si estendeva dalla penisola sorrentina fino al Gargano. La Lega Sannitica, formata inizialmente per scopi religiosi, divenne una potente alleanza militare che costituì un’importante opposizione alla Repubblica Romana.

Il Sannio si configura come un altopiano situato nel centro dell'Italia meridionale, delimitato:

- a nord, dal fiume Sangro e dai territori dei Marsi e dei Peligni;

- a sud, dal fiume Ofanto e dal territorio dei Lucani;

- a est, dal Tavoliere delle Puglie e dal territorio dei Frentani;

- a ovest, dalla pianura campana e dai territori dei Sidicini, dei Latini e degli Aurunci.

Dalle catene montuose e dalle numerose sorgenti si originano corsi d'acqua fondamentali per l’agricoltura e la pastorizia. Tuttavia, i terreni del Sannio erano prevalentemente poco fertili, anche a causa delle condizioni climatiche sfavorevoli: inverni rigidi, gelate tardive ed estati siccitose. Questo rendeva difficile sostenere una popolazione in crescita. La scarsità di risorse alimentari fu il principale motivo delle migrazioni verso le fertili pianure delle regioni confinanti. Queste migrazioni causarono spesso conflitti con gli agricoltori locali, che vedevano nelle greggi sannitiche una minaccia per le loro colture.

Nonostante queste difficoltà

Nonostante queste difficoltà, il Sannio vantava una rete viaria efficiente, di cui sono ancora visibili tracce. Ad esempio:

- Alife aveva una strada che attraversava l’impervio Matese per collegarsi a Bojano e a Telesia;

- Beneventum era un importante crocevia, da cui si diramavano strade verso Telesia, il Volturno, Teano Sidicino e Rufrae;

- Venafro e Isernia costituivano nodi stradali strategici, con collegamenti verso Beneventum e altre città.

Nonostante la presenza di una rete viaria efficiente, i Romani impiegarono più di 70 anni per sottomettere il Sannio e stabilire colonie latine. Tra queste si ricordano: Realis nel 334 a.C., Frigelle nel 328 a.C., Luceria nel 314 a.C., Saticula nel 313 a.C., Interamna Lirenas nel 312 a.C., Sora nel 303 a.C., Venusia nel 291 a.C., Beneventum nel 268 a.C. e Aesernia nel 263 a.C.

Nel IV secolo a.C., il fiume Sangro segnava per buona parte del suo percorso il confine settentrionale del territorio sannitico. Il Sannio includeva il massiccio montuoso del Monte Meta, alto circa 2.200 metri, situato a ovest della Valle di Comino, vicino all’attuale Alvito. Includeva inoltre la fortezza di Cominium, con l’intera Val di Comino.

Durante il IV secolo a.C., il Sannio si espanse verso nord-ovest, arrivando a includere territori fino al fiume Liri. In questo periodo, città come Atina, Cassino, Arpino, Fregellae, Interamna Lirenas e, presumibilmente, Venafro e Aquinum rientravano nei confini sannitici. Il fiume Ofanto, invece, costituiva il confine meridionale del Sannio e includeva città come Venusia e Ricorsa.

A est, città come Teanum Apulum e Canusium non facevano parte del Sannio, mentre Luceria potrebbe esservi appartenuta. A ovest, il confine attraversava i Monti Trebulani, separando le città dei Sidicini, come Teanum e Cales, dalle città sannitiche di Rufrae, Trebula, Fulcaria, Saticula, Caudium e Calatia.

Durante l’età repubblicana, i Sanniti si trovavano al centro di un territorio di confine conteso e caratterizzato da una complessa rete di città e tribù. Il Sannio rimase un'area strategicamente cruciale, teatro di importanti conflitti e alleanze nel quadro della crescente influenza romana.

La regione del Sannio fu chiamata Safim dai suoi abitanti, Samnium dai Latini e Sanitari dai Greci. Secondo la tradizione antica, i Sanniti sarebbero giunti da nord, attraversando gli Appennini, o da est, provenendo dall’Adriatico. Quando arrivarono nel Sannio, trovarono gli Opici (Osci), un gruppo affine immigrato in precedenza, e ne acquisirono la lingua, l’osco.

La credenza secondo cui i Sanniti sarebbero emigrati dal paese dei Sabini, discendenti degli Spartani, non appare verosimile, soprattutto per l’assenza di grecismi nella lingua osca. Di conseguenza, sia i Sabini sia i Sanniti possono essere considerati popoli italici, ovvero gruppi che parlavano varietà di lingue indoeuropee, la cui esistenza è attestata per la prima volta in Italia durante l’età del Ferro, intorno al 600 a.C.

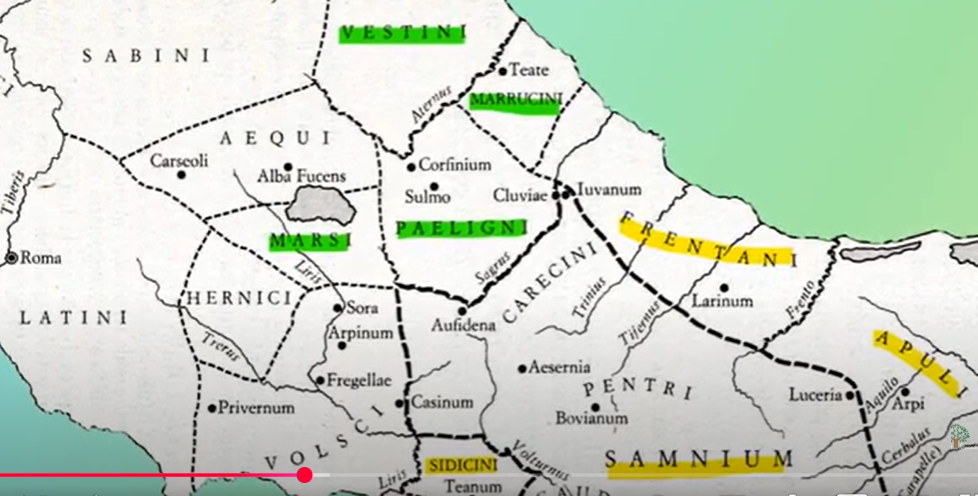

Nel periodo della guerra sociale, emerse la necessità di trovare un termine per designare tutti i popoli di lingua osca, che erano geograficamente separati. Per questo motivo, i dotti romani chiamarono Sabelli le genti che parlavano l’osco. Oggi, gli studiosi usano il termine sabellico per indicare i popoli che parlavano dialetti oschi, come i Peligni, i Vestini, i Marrucini, i Marsi e i Sabelli. Coloro che parlavano l’osco vero e proprio comprendevano i Sanniti, i Frentani, i Sidicini, i Campani, i Lucani, gli Apuli, i Bruzzi e i Mamertini.

Nel 600 a.C. le tribù osche erano distinte e separate, ma nel V secolo a.C. i Sanniti acquisirono il controllo incontrastato del Sannio. Non si può escludere che alcune tribù Sabelli siano nate dalla tradizione del Ver Sacrum (Primavera Sacra), un rituale religioso che spingeva i popoli di lingua osca a migrare lungo gli Appennini, scendendo periodicamente verso le pianure su entrambi i versanti.

Il Ver Sacrum, descritto da Strabone e altri autori, veniva praticato dai Sabelli per affrontare una battaglia, allontanare un pericolo o porre fine a una calamità naturale come una carestia o un’epidemia. In segno di devozione alla divinità Mamerte, promettevano di sacrificare la decima parte di tutto ciò che fosse nato nella primavera successiva. I bambini nati in quel periodo venivano allevati come consacrati e, raggiunta l’età adulta, erano obbligati a lasciare la loro tribù per cercare nuovi boschi e pascoli, seguendo la guida di un animale.

L’animale guida poteva essere un toro, un lupo, un picchio, un orso o un cervo. Il gruppo migrante si stabiliva dove riteneva che l’animale avesse indicato. È probabile che il rituale fosse simbolico e che gli emigranti marciassero sotto un vessillo raffigurante l’animale. Il Ver Sacrum aveva lo scopo reale di risolvere problemi di sovrappopolazione.

Secondo la tradizione,

Secondo la tradizione

Secondo la tradizione, i primi gruppi sacrati a stabilirsi nel Sannio furono condotti da un animale guida (forse un toro) a Roviano, che divenne la culla della loro nazione.

Per le altre zone dell’Italia meridionale, le fonti greche sembrano fornire alcune date significative. Sappiamo così che, all’inizio del V secolo a.C., buona parte dell’Italia meridionale era sotto il dominio politico e culturale dei Greci, mentre una porzione era controllata dagli Etruschi. Poco dopo il 500 a.C., con il crollo della dominazione etrusca in Campania, le genti di lingua osca colsero l’occasione per occupare queste zone, abbandonando le sovrappopolate montagne del Sannio.

I Sabelli si spinsero anche verso ovest, in Campania, dove erano presenti almeno dal 471 a.C., quando, secondo Catone, si ebbe la fondazione di Capua. In realtà, come afferma Velleio, Capua (egli stesso un Sabello) fu fondata molto prima, ma nel 471 potrebbe essere nata la nazione dei Campani, che, per i suoi stretti legami con i Greci, era assai più colta, raffinata e ricca rispetto ai gruppi rimasti sulle montagne.

Le più antiche menzioni dei Sanniti si trovano negli scritti greci del IV secolo a.C. Filisto di Siracusa, nell’undicesimo libro, li nomina come abitanti delle città di Tifernum e Mistia. Il Periplo (circa 350 a.C.) scrive che, sulla costa occidentale d’Italia, i Sanniti erano adiacenti ai Campani. Si impiegava mezza giornata per costeggiare il loro territorio. Sulla costa orientale, superati gli Japigi e il Monte Gargano, si trovava il popolo dei Sanniti, che occupava la zona tra il Tirreno e l’Adriatico. Si impiegavano due giorni e una notte per costeggiare il loro territorio.

Considerando che una giornata di navigazione corrispondeva a circa 30 miglia, possiamo stimare che il territorio sannitico si estendesse per circa 15 miglia sulla costa occidentale, dalla penisola sorrentina al fiume Sillaro, e per circa 75 miglia sulla costa orientale, dal Gargano al fiume Pescara.

Le tribù sannitiche nominate dagli scrittori antichi includevano i Pentri, i Caudini e gli Irpini, tutti avversari di Roma. Erano caratterizzati da un forte senso di nazionalità e affinità, tanto da potersi alleare nella temibile Lega Sannitica. Secondo Livio e Diodoro, la Lega Sannitica esisteva già nel 354 a.C., anno in cui firmò un trattato con Roma. È possibile che la Lega si fosse originariamente formata per scopi religiosi e sacrali. Dopo il 400 a.C., sappiamo dell’esistenza di leghe all’interno di tre popoli Sabelli: i Campani, i Lucani e i Sanniti.

I Pentri, il cui nome contiene la radice celtica pen (sommità), erano un popolo montanaro che abitava la regione del Matese, le sue vicinanze e le valli dei fiumi Trigno e Tiferno. Erano un popolo forte e temibile, considerato la spina dorsale della nazione sannitica. Un numero significativo di essi era concentrato nella valle dominata da Bojano e Sepino. In seguito alle guerre sannitiche, dovettero cedere parte del loro territorio a Roma, ma rimasero tecnicamente indipendenti, sebbene subordinati a Roma, fino alla guerra sociale.

A quel tempo, il termine "Sannita" indicava esclusivamente la tribù dei Pentri, poiché prima del 91 a.C. gli stati tribali dei Caraceni e dei Caudini erano scomparsi, mentre gli Irpini erano considerati un popolo a parte dagli stessi Romani. Dopo la guerra sociale, tutti i Pentri ottennero la cittadinanza romana, ma non facevano parte della stessa tribù romana.

Boiano, Sepino, Frigento e Trevento appartenevano tutte alla tribù romana Voltinia. Oltre a queste, vi erano altri centri abitati dai Pentri, come Alife, Cassino, Venafro e Matelica. Lo stesso vale per Isernia, che divenne colonia latina nel 263 a.C.

Nel 263 a.C., la città fu incorporata in una diversa tribù, la Trementina. Alife, Atina, Cassino e Venafro facevano tutte parte della tribù Tretinoina e furono incluse nella Regione I dell'Italia Augustea.

Per quanto riguarda i Caudini

Per quanto riguarda i Caudini

Per quanto riguarda i Caudini, lo status tribale delle loro città indica che furono inclusi nella tribù romana Falerna. Durante il processo di consolidamento delle loro posizioni ai margini della pianura campana, i Caudini, essendo i più occidentali tra le tribù sannitiche, erano anche i più esposti all’influenza greca proveniente dalla Campania. Di conseguenza, tra tutte le popolazioni sannitiche, i Caudini risultavano i più urbanizzati e i più facili da tenere separati.

Le città principali dei Caudini includevano Caudium, la loro capitale, e tre località situate sui Monti Trebulani o nelle loro vicinanze, a ovest del fiume Volturno: Caiazzo, Trebula e Cales. Anche Telesia, probabilmente la città natale del grande condottiero sannita Gaio Ponzio, e Saticula, divenuta colonia latina nel 313 a.C., erano presumibilmente caudine.

I Caudini vivevano tra le montagne e i margini della pianura campana, occupando il Monte Taburno, i Monti Trebulani, la valle degli Sclero e il tratto centrale del Volturno.

Gli Irpini, invece, erano entrati a far parte della regione che includeva Avellino. Abitavano la parte meridionale del Sannio, comprendente le vallate dell’Ofanto, del Calore e del Sabato. A nord confinavano con i Pentri, forse separati dal fiume Tammaro, mentre a sud erano separati dai Lucani dai Monti Cervialto e Marzano. Si può supporre che gli Irpini somigliassero più ai Lucani che alle altre popolazioni sannitiche.

Sia gli Irpini sia i Lucani erano detti "uomini lupo", dall’osco irp e dal greco lykos (lupo). Dall’epoca della seconda guerra punica, e quindi molto dopo lo scioglimento della Lega Sannitica, gli scrittori antichi spesso menzionano gli Irpini come un popolo Sabello distinto. Questo potrebbe essere dovuto alla politica romana del divide et impera.

Le loro principali città erano Abellinum (l’attuale Avellino), Eclanum, e Maleventum (che divenne Beneventum). Altre città importanti includevano Luceria e Venusia.

Samnium is configured

Samnium is configured as a plateau located in the center of southern Italy. It is bordered to the north by the Sangro River and the territories of the Marsi and the Peligni, to the south by the Ofanto River and the territories of the Lucani, to the east by the Tavoliere delle Puglie and the territory of the Frentani, and to the west by the Campanian plain and the territories of the Sidicini, the Latins, and the Aurunci.

Samnium is predominantly mountainous, with formations of limestone and dolomite that, due to their shape and altitude, made transit difficult but offered safe refuge for the Samnite tribes. The Majella mountains were the refuge of the Caraceni, the Irpinian mountains of the Irpini, Mount Taburno of the Caudini, and the Matese of the Pentri. From these mountain ranges and their numerous springs flow many watercourses, essential for agriculture and livestock farming, both practiced on mostly infertile land due in part to harsh climatic conditions, such as severe winters, late frosts, and dry summers.

The difficulty in producing sufficient food resources for a growing population led the Samnites to migrate toward the surrounding fertile plains, often coming into conflict with local farmers who considered the herds a threat to their crops. Despite an efficient road network—some traces of which remain, such as the road crossing the Matese that connected Alife to Telesia and Beneventum—the Romans took more than seventy years to conquer and integrate Samnium.

In the 4th century BC, the Sangro River marked the northern border of Samnium, which included territories such as Mount Meta and the Comino Valley.

During this period, Samnium expanded toward the Liri River, including cities like Aquino and Venafro. To the south, the border was defined by the Ofanto River, while to the east, cities such as Teanum Apulum and Canusium were not part of Samnium, unlike Luceria, which likely was.

According to tradition, the Samnites were descendants of the Sabines, who moved into Samnium through a ritual known as the Ver Sacrum. This ritual required young people consecrated to the deity Camerta to leave their tribe and found new communities under the guidance of a sacred animal, often symbolically represented on a standard. The necessity of performing the Ver Sacrum was likely linked to overpopulation.

The main Samnite tribes were the Pentri, the Caudini, and the Irpini.

The Pentri, a mountain people, occupied the region of the Matese and the valleys of the Trigno and Tiferno rivers.

The Caudini, located between the mountains and the Campanian plain, were the most urbanized and influenced by Greek culture.

The Irpini, known as "wolf-men," inhabited the valleys of the Ofanto, Calore, and Sabato rivers, bordering the Pentri to the north and the Lucani to the south.

After the Samnite Wars, the Samnites lost much of their territory to Rome, maintaining partial autonomy until the Social War, during which they gained Roman citizenship. From then on, the Samnite tribes were integrated into the Roman administrative structure.

The first mentions of the Samnites appear in Greek writings from the 4th century BC, describing them as inhabitants of the cities of Tifernum and Mistai. Their territory extended from the Sorrentine Peninsula to the Gargano.

The Samnite League, initially formed for religious purposes, became a powerful military alliance and a significant opponent of the Roman Republic.

Samnium is configured as a plateau

Samnium is configured as a plateau located in the center of southern Italy, bounded:

- to the north, by the Sangro River and the territories of the Marsi and Peligni;

- to the south, by the Ofanto River and the territory of the Lucani;

- to the east, by the Tavoliere delle Puglie and the territory of the Frentani;

- to the west, by the Campanian plain and the territories of the Sidicini, Latins, and Aurunci.

From the mountain ranges and numerous springs flowed watercourses that were essential for agriculture and pastoralism. However, the land in Samnium was mostly infertile, also due to unfavorable climatic conditions: harsh winters, late frosts, and dry summers. This made it difficult to sustain a growing population.

The scarcity of food resources was the main reason for migrations toward the fertile plains of neighboring regions. These migrations often led to conflicts with local farmers, who saw the Samnite herds as a threat to their crops.

Despite these difficulties

Despite these difficulties, Samnium boasted an efficient road network, remnants of which are still visible today. For example:

- Alife had a road that crossed the rugged Matese mountains to connect with Bojano and Telesia;

- Beneventum was an important crossroads, from which roads branched out toward Telesia, the Volturno River, Teano Sidicino, and Rufrae;

- Venafro and Isernia were strategic road hubs, with connections to Beneventum and other cities.

Beneventum was the main convergence and departure point of Samnium, to the extent that the saying "All roads lead to Beneventum" derives from it.

Realis in 334 BC, Frigellae in 328 BC, Luceria in 314 BC, Saticula in 313 BC, Interamna Lirenas in 312 BC, Sora in 303 BC, Venusia in 291 BC, Beneventum in 268 BC, and Aesernia in 263 BC.

In the 4th century BC, the Sangro River marked much of the northern boundary of the Samnite territory. Samnium included the mountainous massif of Mount Meta, about 2,200 meters high, located west of the Comino Valley, near present-day Alvito. It also included the fortress of Cominium and the entire Comino Valley.

During the 4th century BC, Samnium expanded northwestward, reaching as far as the Liri River. At that time, cities such as Atina, Cassino, Arpino, Fregellae, Interamna Lirenas, and presumably Venafro and Aquinum fell within Samnite territory. The Ofanto River marked the southern border of Samnium and included cities like Venusia and Ricorsa.

To the east, cities such as Teanum Apulum and Canusium were not part of Samnium, while Luceria may have been. To the west, the border crossed the Monti Trebulani, separating the cities of the Sidicini, like Teanum and Cales, from the Samnite cities of Rufrae, Trebula, Fulcaria, Saticula, Caudium, and Calatia.

During the Republican period, the Samnites found themselves at the center of a contested borderland characterized by a complex network of cities and tribes. Samnium remained a strategically crucial region, the setting of major conflicts and alliances as Roman influence continued to grow.

The region of Samnium was called Safim by its inhabitants, Samnium by the Latins, and Sanitari by the Greeks. According to ancient tradition, the Samnites arrived either from the north, crossing the Apennines, or from the east, coming from the Adriatic coast. When they reached Samnium, they found the Opici (or Oscans), a related group who had migrated earlier, and adopted their language—Oscan.

The belief that the Samnites had emigrated from the land of the Sabines, who were supposedly descendants of the Spartans, is unlikely, especially given the absence of Greek elements in the Oscan language. As a result, both the Sabines and the Samnites can be considered Italic peoples, meaning groups that spoke varieties of Indo-European languages, first attested in Italy during the Iron Age, around 600 BC.

During the Social War, the need arose to find a term to designate all Oscan-speaking peoples who were geographically dispersed. For this reason, Roman scholars used the name Sabelli to refer to these Oscan-speaking peoples. Today, scholars use the term Sabellian to indicate the peoples who spoke Oscan dialects, such as the Peligni, Vestini, Marrucini, Marsi, and Sabelli.

Those who spoke true Oscan included the Samnites, Frentani, Sidicini, Campani, Lucani, Apuli, Bruttii, and Mamertini.

In 600 BC, the Oscan tribes were distinct and separate, but by the 5th century BC, the Samnites had established uncontested control over Samnium. It is possible that some Sabellian tribes originated from the tradition of the Ver Sacrum ("Sacred Spring"), a religious ritual that led Oscan-speaking peoples to migrate along the Apennines, periodically descending into the plains on both sides.

The Ver Sacrum, described by Strabo and other authors, was practiced by the Sabelli in response to war, danger, or natural calamities such as famine or plague. In devotion to the god Mamers, they vowed to sacrifice one-tenth of all that was born the following spring. Children born during that time were raised as consecrated individuals and, upon reaching adulthood, were required to leave their tribe to seek new lands and pastures, following the guidance of a sacred animal.

The guiding animal could be a bull, wolf, woodpecker, bear, or deer. The migrating group would settle where they believed the animal had indicated. It is likely that the ritual was symbolic and that the emigrants marched under a standard bearing the image of the animal.

The Ver Sacrum served a practical purpose: to address issues of overpopulation.

According to tradition

According to tradition, the first consecrated groups to settle in Samnium were led by a guiding animal (perhaps a bull) to Roviano, which became the cradle of their nation.

For other areas of southern Italy, Greek sources seem to provide some significant dates. Thus, we know that at the beginning of the 5th century BC, much of southern Italy was under Greek political and cultural control, while a portion was held by the Etruscans. Shortly after 500 BC, with the collapse of Etruscan domination in Campania, the Oscan-speaking peoples seized the opportunity to occupy these areas, leaving the overpopulated mountains of Samnium.

The Sabellians also pushed westward into Campania, where they were present at least as early as 471 BC, the year when, according to Cato, the founding of Capua took place. In reality, as Velleius states—himself a Sabellian—Capua was founded much earlier, but it is possible that the Campanian nation emerged around 471 BC. Due to their close ties with the Greeks, the Campanians were far more cultured, refined, and wealthy than the groups that remained in the mountains.

The earliest mentions of the Samnites appear in Greek writings of the 4th century BC. Philistus of Syracuse, in his eleventh book, names them as inhabitants of the cities of Tifernum and Mistia. The Periplus (ca. 350 BC) reports that on the western coast of Italy, the Samnites were adjacent to the Campanians. Sailing along their territory took half a day. On the eastern coast, beyond the Iapygians and Mount Gargano, lived the Samnites, occupying the area between the Tyrrhenian and the Adriatic seas. Sailing along this stretch of coastline took two days and one night.

Considering that a day of navigation equated to about 30 miles, we can estimate that Samnite territory stretched approximately 15 miles along the western coast, from the Sorrentine Peninsula to the Sillaro River, and about 75 miles along the eastern coast, from Gargano to the Pescara River.

The Samnite tribes named by ancient writers included the Pentri, Caudini, and Irpini, all adversaries of Rome. They were characterized by a strong sense of nationality and kinship, enough to unite in the formidable Samnite League. According to Livy and Diodorus, the League already existed in 354 BC, the year it signed a treaty with Rome. It is possible that the League had originally formed for religious and sacred purposes. After 400 BC, we know of the existence of leagues among three Sabellian peoples: the Campanians, Lucanians, and Samnites.

The Pentri, whose name contains the Celtic root pen (summit), were a mountain people inhabiting the Matese region, its surroundings, and the valleys of the Trigno and Tifernus rivers. They were strong and fearsome, considered the backbone of the Samnite nation. A significant number of them were concentrated in the valley dominated by Bojano and Sepino. Following the Samnite Wars, they had to cede part of their territory to Rome but remained technically independent—though subordinate to Rome—until the Social War.

At that time, the term "Samnite" referred exclusively to the Pentri tribe, since by 91 BC the tribal states of the Caraceni and Caudini had disappeared, and the Irpini were considered a separate people even by the Romans. After the Social War, all Pentri obtained Roman citizenship, but they were not part of the same Roman tribe.

Bojano, Sepino, Frigento, and Treveno (Trevendo) all belonged to the Roman tribe Voltinia. In addition to these, there were other centers inhabited by the Pentri, such as Alife, Cassino, Venafro, and Matelica. The same applied to Isernia, which became a Latin colony in 263 BC.

In 263 BC, the city was incorporated into a different tribe, the Trementina. Alife, Atina, Cassino, and Venafro all belonged to the Roman tribe Tretinoina and were included in Region I of Augustan Italy.

As for the Caudini

As for the Caudini, the tribal status of their cities indicates that they were included in the Roman tribe Falerna. During the process of consolidating their position on the edges of the Campanian plain, the Caudini—being the westernmost of the Samnite tribes—were also the most exposed to Greek influence coming from Campania. As a result, among all the Samnite peoples, the Caudini were the most urbanized and the easiest to keep distinct.

The main cities of the Caudini included Caudium, their capital, and three localities situated on or near the Monti Trebulani, west of the Volturno River: Caiazzo, Trebula, and Cales. Telesia, probably the birthplace of the great Samnite leader Gaius Pontius, and Saticula, which became a Latin colony in 313 BC, were also likely Caudinian.

The Caudini lived between the mountains and the edge of the Campanian plain, occupying Mount Taburno, the Monti Trebulani, the Sclero Valley, and the central stretch of the Volturno River.

The Irpini, on the other hand, had become part of the region that included Avellino. They inhabited the southern part of Samnium, including the valleys of the Ofanto, Calore, and Sabato rivers. To the north, they bordered the Pentri, perhaps separated by the Tammaro River, while to the south they were divided from the Lucani by the Cervialto and Marzano mountains. It can be assumed that the Irpini resembled the Lucani more than the other Samnite peoples.

Both the Irpini and the Lucani were known as “wolf-men,” from the Oscan word irp and the Greek lykos (wolf). From the time of the Second Punic War, long after the dissolution of the Samnite League, ancient writers often mentioned the Irpini as a distinct Sabellian people. This may have been a result of the Roman divide et impera policy.

Their main cities were Abellinum (modern-day Avellino), Eclanum, and Maleventum (which became Beneventum). Other important cities included Luceria and Venusia.